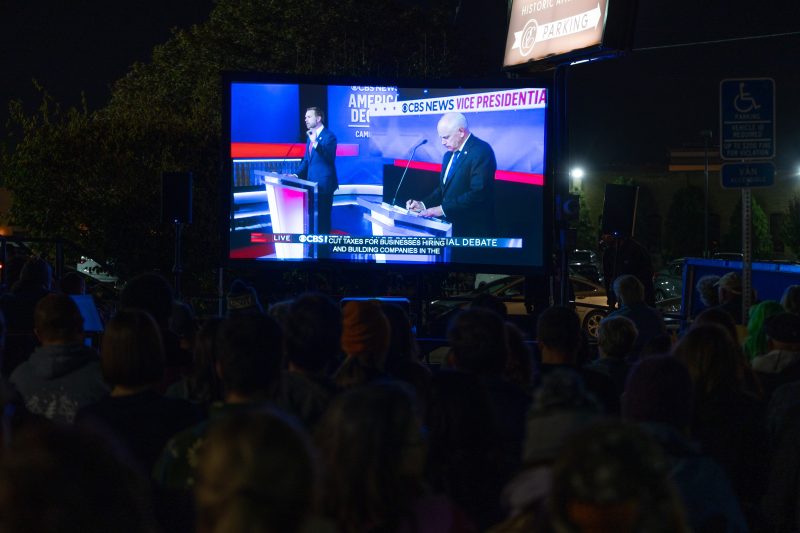

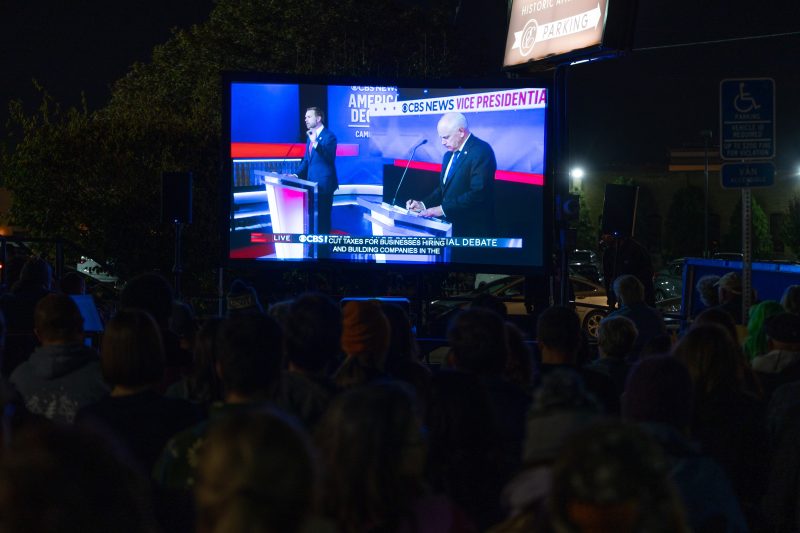

Given the disastrous damage wrought by Hurricane Helene — a storm that rapidly grew to a Category 4 storm thanks to unusually warm water in the Gulf of Mexico — the issue of climate change was among the first topics broached during Tuesday evening’s vice-presidential debate.

The answers given by Sen. JD Vance (R-Ohio) and Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz (D) were effective at conveying the wide gulf between the parties on the subject. But they also highlighted the way in which the Republican position depends heavily on GOP opposition to clean energy a decade ago.

Vance was presented with the question first, asked how a second Donald Trump administration would try to address climate change. Vance began by recognizing the ongoing suffering in regions hit by Helene before acknowledging that climate change is “a very important issue” with a lot of people “worried about all these crazy weather patterns.”

He didn’t continue down that path.

“I think it’s important for us, first of all, to say Donald Trump and I support clean air, clean water,” Vance said. “We want the environment to be cleaner and safer.”

This is very much in keeping with Trump’s rhetoric on the issue. Trump has long responded to questions about climate change by talking, instead, about the environment broadly and about his purported passion for clear air and water (despite his administration rolling back protections for those things) — to the point that it was reasonable to ask whether he knew what climate change actually entailed.

Vance, though, then acknowledged the actual issue. Sort of. He suggested that it be stipulated, just for the sake of argument, that carbon-dioxide emissions are driving increased warming, which is a bit like stipulating that a dropped object will fall toward the Earth. (The CBS moderators would later note the scientific consensus on this point that Vance tried to present as contentious.) If that is the case, he said, what you would want to do is “reshore as much American manufacturing as possible. You’d want to produce as much energy as possible in the United States of America, because we’re the cleanest economy in the entire world.”

The policies of the Biden administration, he said, had instead resulted in “more energy production in China, more manufacturing overseas, more doing business in some of the dirtiest parts of the entire world.”

This is a variant of a common line of rhetoric on the right, one he made more explicit later.

“If you’re spending hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars of American taxpayer money on solar panels that are made in China,” he said, “number one, you’re going to make the economy dirtier. We should be making more of those solar panels here in the United States of America.”

This is an argument, in short, for slowing the rollout of clean energy technology. But there is a big reason we don’t currently make more solar panels (and more batteries and more of other components of clean energy) in the United States: Republican opposition to investing in the clean-energy sector a decade ago.

When Barack Obama won the 2008 election, he did so handily, promising a pivot away from the policies of President George W. Bush and a robust response to the still-unfolding economic crisis. That included a commitment to address climate change, at that point an issue that sat largely outside of partisan bickering. Former House speaker Newt Gingrich (R) lent his voice to taking steps to combat warming. Trump signed onto an ad in the New York Times that advocated the same.

During Obama’s first term, though, the fossil fuel industry — a central driver of carbon-dioxide emissions — began leaning on its political allies to slow the embrace of technologies such as electric vehicles, wind turbines and solar panels. Thanks in part to Obama’s embrace of what was then referred to as the “green economy,” Republicans rapidly turned against such efforts.

Obama had promised to invest heavily in America’s efforts to build out infrastructure that would allow the United States to lead on the manufacture of green technologies.

“I’ll invest $150 billion over the next decade in affordable, renewable sources of energy — wind power and solar power and the next generation of biofuels,” he said when accepting the Democratic nomination in 2008, “an investment that will lead to new industries and 5 million new jobs that pay well and can’t ever be outsourced.”

His administration pressed forward in that direction. By 2012, though, as Obama was seeking reelection, this position had become a point of attack. The failure of the solar company Solyndra, a beneficiary of federal loan guarantees, was presented by Republicans as a demonstration of the flaws in investing in domestic green manufacturing. (The program in which Solyndra was participating went on to make money for the government.) Obama’s 2012 opponent, former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney, pivoted from his past embrace of addressing climate change to insisting that the government not offer subsidies to green technologies.

“His plan is to let the oil companies write the energy policies,” Obama said of Romney during a debate that year. “So he’s got the oil-and-gas part, but he doesn’t have the clean-energy part. And if we are only thinking about tomorrow or the next day and not thinking about 10 years from now, we’re not going to control our own economic future.”

“Because China, Germany, they’re making these investments,” Obama continued. “And I’m not going to cede those jobs of the future to those countries. I expect those new energy sources to be built right here in the United States.”

It was not entirely up to him, of course, and largely thanks to opposition from congressional Republicans, the United States ended up essentially ceding those industries to foreign competitors, including China. Meaning that Vance and other Republicans (such as Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene [Ga.]) can now argue against the implementation of lower-emission technologies like electric vehicles by describing them as a boon for China. Meaning, too, that Vance can fume about how these industries should be domestic — exactly what Obama was advocating a decade ago.

In response to Vance’s comments, Walz pointed out that the Inflation Reduction Act had included funding for increasing domestic manufacturing of clean energy jobs, including in their home states of Ohio and Minnesota. He pointed out, too, that this was occurring alongside a surge in domestic oil-and-gas production.

“We are seeing us becoming an energy superpower for the future,” he said, “not just the current.”

He also twisted the knife a bit, noting that Trump had in the past referred to climate change as a “hoax” and that Trump had welcomed oil industry executives to Mar-a-Lago, where he suggested that a $1 billion contribution to boost his campaign would result in a fossil-fuel-friendly president. Walz didn’t mention that Trump’s presidency had included withdrawing the United States from an international climate compact aimed at, among other things, getting competitors such as China to take stronger steps to combat climate change.

But, of course, the point isn’t that Vance is uninformed about climate change or the efforts to reduce carbon-dioxide emissions. The point is that Vance’s role is to present an argument that will convince non-fossil fuel executives to support Trump’s presidential candidacy, and that Democrats-are-insincere and create-more-jobs-here is the argument he’s chosen.

Credit for the viability of those arguments can be given to the Republican Party of a decade ago.